Curiosity and Freedom: The Unsung Pillars of Scientific Discovery

How Alfred Russel Wallace’s Unorthodox Inquiry Challenges the Boundaries of Mainstream Science

Curiosity, intellectual freedom and Science

Curiosity killed the cat? Perhaps, but lack of curiosity or insufficient curiosity kills Science.

Did Curiosity Really Kill the Cat?

Curiosity in one’s work is incessantly asking questions about “How?” and “Why?”.

Nurturing Your Child’s Innate Curiosity: A Labor of Love

Of course children are doing this all the time, but usually they address these questions to adults, and when they try to answer these questions by themselves, they can be in danger because they do not yet have adequate knowledge and experience to fully appreciate the answers. Scientists usually have both knowledge and experience, but their curiosity may have diminished, sometimes completely. Without curiosity Science dies.

Scientists who are not curious about the Unknown and the Unexplained infect Science with a dangerous disease. In principle this fact is well known. For instance, in the opening section of a 2007 report of the European Research Council entitled “What Makes Scientists Creative?” we read these words:

Humans are curious by nature and have been seeking knowledge about the universe, our natural environment, our past and future since ancient times. Scientists exhibit a heightened level of curiosity. They go further and deeper into basic questions showing a passion for knowledge for its own sake.

Curiosity is the driving force of basic, or pure, science. The desire to go beyond the established frontiers of knowledge, to explore the boundaries of discipline and to resolve unanswered questions, is motivated essentially by human inquisitiveness. (Italics, mine.)

But it is one thing is to know certain truth “in principle”, and quite another is to notice the cases in which the principle should be applied, but is not.

Curiosity is Not Enough: Freedom is Essential

Lack of curiosity, intellectual indifference and laziness – they all kill Science. But even when curiosity is present, Science will not grow as it could – and should - without total intellectual freedom.

Freedom is essential

Bertrand Russell, was well aware of the dangers for Science coming not only through the political use of Science, but also from within Science itself. He warned us:

Those to whom intellectual freedom is personally important may be a minority in the community, but among them are the men of most importance to the future. We have seen the importance of Copernicus, Galileo, and Darwin in the history of mankind, and it is not to be supposed that the future will produce no more such men. If they are prevented from doing their work and having their due effect, the human race will stagnate, and a new Dark Age will succeed, as the earlier Dark Age succeeded the brilliant period of antiquity. New truth is often uncomfortable, especially to the holders of power; nevertheless, amid the long record of cruelty and bigotry, it is the most important achievement of our intelligent but wayward species. (Italics, mine.)

New truth is, indeed, often uncomfortable and the history of Science tells how scientists who were asking questions “why?” and “how” have been treated. Learning about how such processes took place in the past enables us to be more sensitive to very same things happening now, all around us. The battle of the Titans still takes place between Science and religion, but it also can be seen within Science itself.

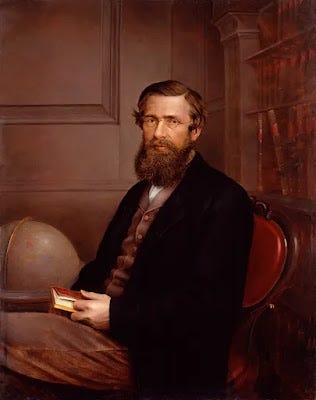

The Curiosity of Alfred Russel Wallace

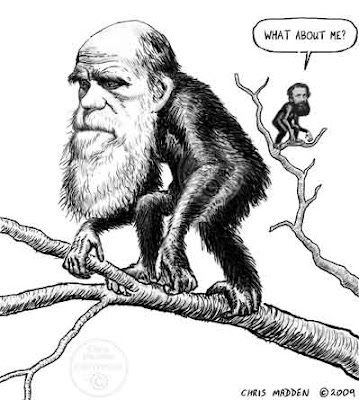

A good example is the case of research into the paranormal, and I want to give examples here of two distinguished scientists who were more curious than the rest of the “mainstream” in their time. The first one of these two is Alfred Russel Wallace, known as the co-founder of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution.

Was he really a co-founder or the originator? This question is still being debated, sometimes fervently. In 2006 Roy Davies, who was researching Darwin’s case for the BBC, summarized the story in his book “The Darwin Conspiracy. Origins of a Scientific Crime.”

Now, I am convinced that Charles Darwin – British national hero, hailed as the greatest naturalist the world has ever known, the originator of one of the greatest ideas of the nineteenth century – lied, cheated and plagiarised in order to be recognised as the man who discovered the theory of evolution.

Charles H. Smith, Science Librarian and Professor of Library Public Services at Western Kentucky University, created a whole website devoted exclusively to the heritage of Alfred Russel Wallace. After examining all the evidence concerning the extent and the priority of both Darwin’s and Wallace’s contributions, he takes a more careful position:

Question: Did Darwin really steal material from Wallace to complete his theory of natural selection?

Answer: Maybe, though the evidence is something short of compelling.

Alfred Russel Wallace

The fact is that Alfred Russel Wallace diverged from Darwin’s purely materialistic position, and therefore had to be punished by those scientists who took it as their creed that anything that goes beyond materialism is either not worthy of their attention or simply wrong. Alfred Wallace was more curious than most of his colleague scientists and his curiosity was not well received. The result was that, today his works are mostly unknown or ignored.

What happened?

Darwin and Wallace Part Company

Around 1865, six years after Darwin published his celebrated “On the origin of species”, Wallace, who was more open-minded than Darwin, became seriously interested in research on faculties of the human mind, including what is called popularly “supernatural – respecting which Darwin did not show any interest at all. Darwin knew all about it in advance, and he did not want to look at the facts, the subject was simply boring for him.

“I wonder why. I wonder why.

I wonder why I wonder.

I wonder why I wonder why

I wonder why I wonder!”

So wrote Richard Feynman, the famous American physicist and Nobel Prize winner, in his book "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" - Adventures of a Curious Character”. Darwin and many others who held important positions in society, industry and politics, did not wonder and did not want to wonder.

Here is what happened.

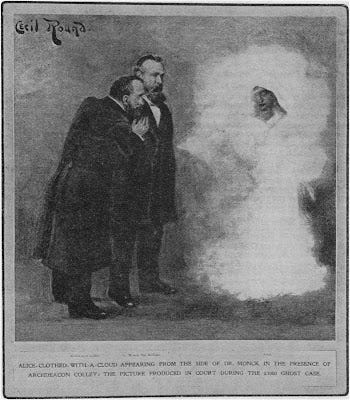

In 1866, after some experimenting on his own, Wallace published his first book on this subject: “The scientific aspects of the supernatural: indicating the desirablenessof an experimental enquiry by men of science into the alleged powers of clairvoyants and mediums.”

He was simply drawing the attention of scientists to the phenomena that he considered important and in need of a serious scientific inquiry. The response that Wallace received revealed a great deal about the level of curiosity that is supposed to be one of the major characteristics of a scientific mind.

Augustus deMorgan, the British mathematician who established the foundation for modern logic (de Morgan laws) was one of the very few who responded with understanding. He confessed, in a letter to Wallace, that he observes the reactions of his students to their exposure to the unknown, and by their reactions can tell whether they are “men of science” or not.

Wallace invited a number of respected scientists – including the noted physicist, John Tyndall – to assist in his investigations into psychic phenomena. His idea was to create a new branch of Anthropology. He also invited convinced Darwinist, T.H. Huxley. Huxley refused the invitation writing: “It may all be true, for anything I know to the contrary, but really I cannot get up any interest in the subject.” Wallace pressed him and Huxley stated that he’d “heard enough of spirit communications to know that they were so much nonsense” and “It’s too amusing to be a fair work, and too hard work to be amusing”. (Keep in mind that Huxley was a self-taught biologist in the days when biology was rather primitive, and became one of the finest comparative anatomists of his day. However, he does seem to have had some political motivations. It is said of Huxley that “Before him, science was mostly a gentleman’s occupation, after him, science was a profession.”).

As for Darwin, he only once sat in a séance, in 1874 – or almost did. When the affair was about to start, Darwin suddenly jumped to his feet and left the room. “The Lord have mercy on us all, if we have to believe in such rubbish" – he commented. His wife Emma, who was there, explained, "He won't believe it, he dislikes the thought of it so very much”. That tells us about the quality of Darwin’s curiosity – a sine qua non condition, without which Science dies. Perhaps we can better understand now why it is said of him that he “lied, cheated and plagiarised in order to be recognised as the man who discovered the theory of evolution” (Davies, R., 2008. The Darwin Conspiracy. Golden Square, London, p. 162). This raises, of course, the interesting question that might be studied scientifically: Does a lack of curiosity also correlate with a lack of character?

The Encyclopedia Universalis Twists the Truth

Alfred Wallace’s scientific curiosity that drove him for over forty years is nowadays considered proof that he was an “eccentric”. In the French Encyclopedia Universalis, esteemed by many as a reliable source, in an entry on Alfred Russel Wallace by Jacqueline Brossolet, "archiviste documentaliste à l'Institut Pasteur", she comments on this curiosity of his in just one sentence:

“At the end of his life, he became interested in sociology, anthropology and human evolution: On Miracles and Modern Spiritualism (1875), Studies Scientific and Social (1900), Man's Place in the Universe (1903). In 1905, he wrote his autobiography My Life.”

Alfred Wallace’s first publication on the subject of paranormal appeared in 1866 – hardly at the “end of his life”, since Wallace died in 1913! If Encyclopedia Universalis is supposed to represent the position of “mainstream science”, in this case it is doing it well - by ignoring inconvenient facts and distorting the truth. But isn’t that what Science accuses Religion of doing?

Wallace’s story underscores the perils of suppressing curiosity and intellectual freedom. When scientists are discouraged from exploring unconventional ideas, the pursuit of truth suffers. The history of science is replete with examples of once-dismissed ideas—such as continental drift or heliocentrism—later validated through persistent inquiry. Wallace’s marginalization serves as a cautionary tale: dismissing unorthodox ideas without investigation risks stifling the very innovation that drives progress. Wallace’s call for scientific inquiry into the paranormal was not an endorsement of unverified claims but a plea for rigorous study—an approach that embodies the scientific method. By contrast, the reflexive dismissal of such topics by his peers reflects a failure of curiosity, undermining the spirit of inquiry.

We will see soon that a similar fate has been bestowed upon another curious scientist, a contemporary of Wallace, William Crookes. Therefore we will be justified to be become curious as to whether, by some chance, we are not dealing here with a rule rather than with an exception?

Kottler - Alfred Russel Wallace, the Origin of Man, and Spiritualism 1974

Whom to believe?

Our beliefs do matter – whether we are a scientist or a priest. They influence our choices, conscious and unconscious. Our choices influence our reality; they influence the choices of other people. The “butterfly effect” may be at work, when one flap of a butterfly wing dramatically changes the weather pattern on the planet according to Chaos Theory. Assigning a very small probability to such an effect may depend on our insufficient knowledge of causes and of circumstances.

We have seen that we should not believe Encyclopedia Universalities in everything that we find there. So, whom to believe?

I like to say: “I do not want believe. I want to know.” Isn’t knowledge better than belief? And yet things are somewhat complicated. Why? Because in some cases when I believe that I know, in reality I do not know. On the other hand I may know that I believe that I know which prevents me – to some extent – from making errors.

There is an error in Encyclopedia Universalis – does it mean that we should not rely on encyclopedias in general? Never? But then, what should we rely upon? Experts? Which experts? Experts make errors as well. Experts often do not agree with each other. Sometimes they fight and they fight violently. Example: In the book “The Neanderthal Enigma”, p. 89, James Shreeve relates a story when, during a conference in Zagreb, one anthropologist, who had dated an archaic sapiens skull to more than 700,000 years, started yelling and charged the podium when another anthropologist (the one speaking at the podium) claimed that he had dated it to less than half that age. A third anthropologist had to use physical force to separate the two, one of whom obviously intended to do bodily harm to the other. Similar fights between “experts” are usually hidden from the eyes of the public, yet they do occur, especially during conferences. The public at large, however, is mostly exposed to a relatively stable “mainstream science” point of view, one which, now and then, undergoes dramatic revolutions.

What to do?

So, what should we believe and whom should we believe? Let me quote here the advice given by Bertrand Russell:

There are matters about which those who have investigated them are agreed; the dates of eclipses may serve as an illustration. There are other matters about which experts are not agreed. Even when the experts all agree, they may well be mistaken. Einstein’s view as to the magnitude of the deflection of light by gravitation would have been rejected by all experts twenty years ago, yet it proved to be right. Nevertheless the opinion of experts, when it is unanimous, must be accepted by non-experts as more likely to be right than the opposite opinion. The scepticism that I advocate amounts only to this:

(1) that when the experts are agreed, the opposite opinion cannot be held to be certain;

(2) that when they are not agreed, no opinion can be regarded as certain by a non-expert; and

(3) that when they all hold that no sufficient grounds for a positive opinion exist, the ordinary man would do well to suspend his judgment.

This may seem like a reasonable approach, but should we believe Bertrand Russell? Russell was certainly a first class philosopher, an expert in his domain, but what do other experts have to say on the same or similar subjects? Do experts agree on the subject of believing?

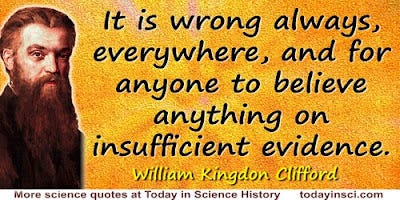

Clifford’s Solution

William Kingdon Clifford, a great British mathematician and also a philosopher, wrote in his essay “Ethics of Belief”:

To sum up: it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.

Even if we accept the above, then we have the next pending question: when can – or should - the evidence be considered as sufficient? Suppose we do want to know the Truth, how do we get to it? Perhaps Truth is so far away that we will never get there? Perhaps it is impossible? We are human beings, with our limited senses, our limited capacities, limited time and limited resources.1 Can we ever really get to the Truth? Isn’t it better, simpler, more efficient, to stay with just what “resonates with us” – as many New Agers declare – and be done with it?

Somehow it is almost automatic that when we meet two opinions on a given subject, one contradicting the other, then we tend to think that the truth is somewhere in the middle. But is that always the case? What if one person is lying? What if one of the persons has mental problems, or is being somehow rewarded for distorting the truth, while the other one is totally honest? In order to avoid making errors in our judgments we should always ask the question “Who says so? And go to the very sources, check their reliability, collect as much information as possible.

Nowadays, thanks to the internet, this is possible for even ordinary people as it never was before in history. At the same time, perhaps those who do not want the truth known are just as busy confusing the matter by publishing disinformation.

Curiosity and intellectual freedom are the twin pillars of scientific progress. Alfred Russel Wallace’s story reminds us that science thrives when it embraces the unknown, even when it challenges prevailing norms. To safeguard the future of science, we must nurture curiosity, protect intellectual freedom, and remain vigilant against the dogmatism that can arise within science itself. Only by fostering an environment where questions are welcomed and inquiry is unbounded can we ensure that science continues to illuminate the mysteries of the universe.

Coming next: Language Barriers Make Knowledge Barriers

Random Background Thoughts at Time of Writing

P.S.1. This morning I received email from Dr Gina Langan inviting me to " become a Guardian of Logos, protector of Absolute Truth."

I followed my own advice "when you see a piece written by someone, even by an “authority”, whether or not they quote or cite sources – consider it as just an opinion, not as a “proof”."

What I have found is that Dr. Gina Langan won the 1989 Belgian Women's Chess Championship and she completed bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees in clinical psychology at Wayne State University in less than five years.

Not enough information for me to decide if I want to join the "Guardians of Logos and protectors of Absolute Truth". But I am seriously considering the offered seven days free trial.

P.S.2. Finished reading “Atlas Shrugged” by Ayn Rand. What I liked is the “happy end”. What strikes me is the evident dislike of any kind of mysticism - indiscriminately. At the end the group of co-linear “good”, “thinking” and “creative” people” escapes the fate of the totally corrupt system. I wonder what would Ayn Rand say about today's political and economic reality that would have to include China?

Chris Langan seems to be more careful when talking about mysticism. For instance he writes:

"One cannot be an enemy of Truth and a servant of God. By hating truth and serving evil even under the aegis of organized religion, one earns the same fate as that of atheists who misidentify God as a misdefined version of "science". Worshipping a false God is as bad as, or worse than, worshipping no God at all."

But for him God stands for "Global Operator-Descriptor (GOD)”"

P.S.3. 29-03-23 9:11 Reading E. Prugovecki, "Dawn of the New Man". I had no idea what kind of a book it will be. Surprise-surprise! Here is a piece:

"As Kant had pointed out in his Critique of Pure Reason, there are synthetic judgments that transcend reason and empirical proof. One had to undergo the kind of mystical experience that Anita had allowed me to share with her in order to achieve such deep faith in the Destiny of Man as she already had.

I was also reminded of the metaphysical visions of Plotinus - the last of the great Neoplatonists - who more than two millennia earlier wrote that, when we are “divinely possessed and inspired,” we see not only the nous, the Spirit, but also the One, the Divine. And when we are thus in contact with the Divine, we cannot reason or express the vision in words: “At the moment of touch there is no power whatever to make any affirmation; there is no leisure; reasoning upon the vision is for afterwards.”

Could it be-I asked myself while savoring the memory of my mental and physical union with Anita-that Plotinus’s experiences of “ecstasy” were some form of precognition, rather than just the dreams of a gentle and noble mind turning away from the spectacle of ruin and misery in the world in which he actually lived?"

and then:

"“I think that what Liu as driving at is the old mind-body philosophical question,” intervened Leonardo. “How does the mind interact with the body? And what is free will?”

Most interesting!"

Further in the same book:

"The lowest estimates on the number of civilization in our galaxy run into the millions. But many might be aquatic ones, not even fully aware of the vast Universe surrounding them. Others might be totally satisfied with their lives on the planets they inhabit. And amongst those that are not, many might be so far ahead of us that they are not interested in making contact with such a puny race as mankind still is. Among those that might be at our stage of development, the enormity of the spatial distances separating them from us and the limit imposed on space travel by the speed of light provides a very effective barrier against direct contact.”

“But what about worm holes, hyperspace, or superstring spatio-temporal dimensions that might make such contacts almost instantaneously possible?” “Ha! Ha!” laughed Ahmed. “I would have thought that as a quantum cosmologist you were well aware that all those Old Era speculations were just mathematical junk, without any firm physical foundation. I wonder why serious scientists ever published such nonsense in the Old Era, especially since their mathematics was even worse than their physics”

I shook my head sadly. “Not only published, but vigorously promoted it. That’s why I stopped being a quantum cosmologist in the Old Era: the so-call ‘leading scientists’ were selling what they sometimes called ‘sexy’ theories basically the same way whores were selling their charms in red light districts. The ‘glitzier’ an idea sounded, regardless of whether it was mathematically and physically sound, the easier it was to sell it!”

.....

"I shrugged. “Those were very different times, Ahmed. One leading physicist in those times by the name of Richard Feynman, who was more astute than the rest, talked about the ‘pack effect’: the pre-dilection of the mainstream scientists during the closing decades of the Old Era to blindly follow fashions dictated by a few self-appointed leaders, regardless of the intrinsic merits of the theories they were advancing. And, as the great physicist Werner Heisenberg noted in his very last paper, published in 1976 O.E., even when the advanced physical theories might have been good, they were ‘spoiled’ by ‘very poor philosophy.’ "

But there is hope:

"... telepathic signals were not subject to Einstein’s relativistic laws"

...

"The prevalent theory that paranormal scientists subscribed to was that since spacetime was fundamentally quantum rather than classical in its nature, its spacetime events were not “pointlike,” but stochastically extended in their structure. Thus, strictly speaking, at the quantum level there was not a sharp dividing line between past, present and future even locally. Telepathic communication was supposed to be able to take advantage of this fact by deforming the local probabilistic potentialities into stochastically more extended forms, thus enabling meaningful, albeit sporadic and only stochastically reliable, instantaneous communication over enormous spacetime separations."

I like it!

P.S.4. 30-03-23 8:46 Finished reading E. Prugovecki, "Dawn of the New Man". Lot of "romantic" stuff there, quite unexpected! It is a pity that with so much stressing of telepathy and "mind-merging" our Quantum Cosmologist has nothing to say about mathematics and physics of the future society, where mind reading plays such an important role.

I am moving back to reading McGilchrist - "The Matter with Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World" (2021). And to Chris Langan's Metatheories. Very important.

P.S.5. 30-03-23 12:26 Two brain hemispheres with complementary roles. To survive and eat but not get eaten. Complementarity and duality. Matter-antimatter, universe - anti-verse, so below as above (but not exactly "so"), mind and matter, space and time, waves and particles, bosons and fermions ... what else? Other examples and parallels?

P.S.6 12:52: The Epoch Times: "“Contemporary AI systems are now becoming human-competitive at general tasks and we must ask ourselves: Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth? ..."

P.S.7. 12:55 Reading E. Prugovetski "Stochastic phase space kinematics of the photon" (1978). It seems almost no one paid any attention to this paper.