Curiosity Over Conformity: The Battle for True Scientific Progress

How Dogmatism, Language, and Resistance to Inquiry Stifle Discovery

Curiosity and intellectual freedom are the lifeblood of scientific discovery. From Galileo’s challenge to geocentric dogma to Einstein’s redefinition of space and time, science advances when minds question norms and explore the unknown. Yet, conformity—whether through cultural barriers, rigid beliefs, or dismissal of unconventional ideas—threatens progress. Here we explore three obstacles to scientific curiosity: language and cultural insularity, dogmatism within science, and resistance to unexplained phenomena. It will only be by overcoming these barriers that we might be able to illuminate the universe’s mysteries.

Language Barriers Make Knowledge Barriers

As I noted at the end of the previous post:

Somehow it is almost automatic that when we meet two opinions on a given subject, one contradicting the other, then we tend to think that the truth is somewhere in the middle. But is that always the case? What if one person is lying? What if one of the persons has mental problems, or is being somehow rewarded for distorting the truth, while the other one is totally honest? In order to avoid making errors in our judgments we should always ask the question “Who says so? And go to the very sources, check their reliability, collect as much information as possible.

Nowadays, thanks to the internet, this is possible for even ordinary people as it never was before in history. At the same time, perhaps those who do not want the truth known are just as busy confusing the matter by publishing disinformation.

Curiosity and intellectual freedom are the twin pillars of scientific progress. Alfred Russel Wallace’s story reminds us that science thrives when it embraces the unknown, even when it challenges prevailing norms. To safeguard the future of science, we must nurture curiosity, protect intellectual freedom, and remain vigilant against the dogmatism that can arise within science itself. Only by fostering an environment where questions are welcomed and inquiry is unbounded can we ensure that science continues to illuminate the mysteries of the universe.

In this post, I want to point out that, of course, for those who can’t read English there will be additional problems. Analysis shows, for instance, that:

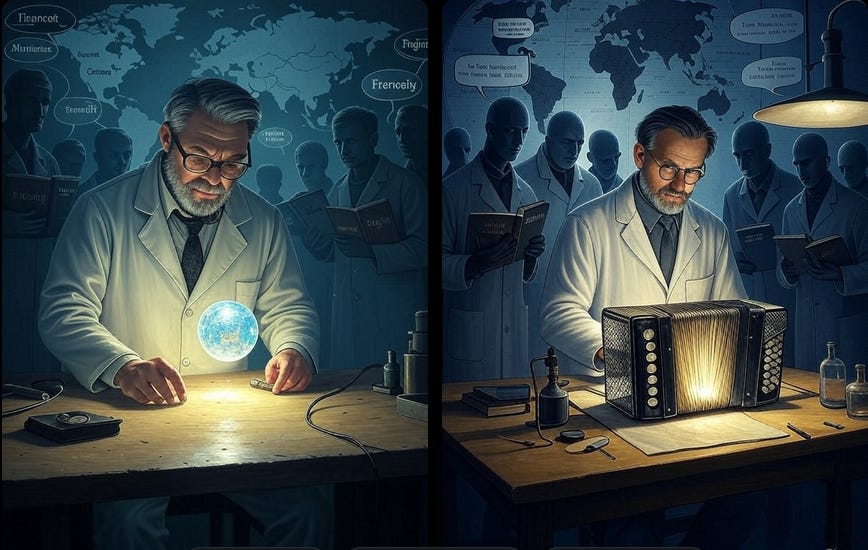

Throughout the 20th century, international communication has shifted from a plural use of several languages to a clear pre-eminence of English, especially in the field of science. This paper focuses on international periodical publications where more than 75 percent of the articles in the social sciences and humanities and well over 90 percent in the natural sciences are written in English. The shift towards English implies that an increasing number of scientists whose mother tongue is not English have already moved to English for publication. Consequently, other international languages, namely French, German, Russian, Spanish and Japanese lose their attraction as languages of science. Many observers conclude that it has become inevitable to publish in English, even in English only.

Here is the graph taken from globaldev blog publication "Removing language barriers for better science":

Figure 1: Shares of languages in science publications, 1880–2005: overall average percentage for biology, chemistry, medicine, physics, and mathematics. Sources: Tsunoda 1983; Ammon 1998; the author’s own analysis, with the help of Abdulkadir Topal and Vanessa G. Figure from: Ammon, U., 2010. p.115

In countries such as France, where great emphasis is placed on everyone speaking the same language, and the language is held up as the proof of allegiance to “French values”, (whether that is consciously or unconsciously felt by the population), and where the educational system is such that languages are mostly taught following archaic methods which usually prevent citizens from being able to have even simple conversations with English speakers, even after years of English lessons at school, there is a serious and growing isolation caused by the very small number of French people who learn English. This is dangerous to science in France and ultimately dangerous to France itself.

One of the main examples of this is the statistical evidence that France is at least 40 years behind other Western countries in social and humanistic sciences. In the top 100 world universities, France has four entries in the rankings: PSL University (Paris Sciences & Letters) comes in as 26, Institut Polytechnique de Paris as 48, Sorbonne as 60, and Université Paris-Saclay comes in at 69. That is a shocking fact for the country that is the home of “liberte, egalite, fraternite.” Of the top 10 universities in the world, 5 are in the U.S., 4 in UK, and one in Switzerland (ETH). If France intends to catch up, it’s going to have to speak English.

In Science it is so, that more often than not we are forced to rely on the evidence transmitted to us by someone else via language. It is impossible to observe certain unique phenomena again. For instance we are not able to repeat the observation of a supernova explosion of 1572. But astronomers, at least many of them, rely on its description given by Tycho Brahe – even though he was strongly opposed to the heliocentric system of Copernicus.

You Shall Know Them by Their Fruits

Dogmatism within science stifles curiosity by prioritizing established norms over evidence.

From what we can read about him, William Crookes was certainly one of the most skillful and honest scientists of his time and his awards testify to that. Therefore, I think, his evidence should be taken under serious consideration. Well, unless someone has prejudices ….

After checking the encyclopedias, next, we check Wikipedia. Wikipedia is not always reliable, nevertheless it often points to some relevant additional information. In French Wiki the additional information is given in just few lines:

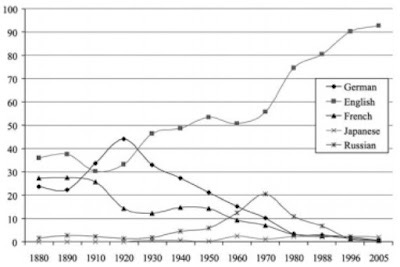

“Recherches concernant des phénomènes inexpliqués

Exemple d'expérience : 1) Un accordéon neuf, acheté par Crookes, est placé dans une boite grillagée. 2) En présence de Monsieur Home, l'accordéon joue une mélodie « tout seul ». La suite de la phrase coupée en fin de page est : « Alors l'instrument continua à jouer, personne ne le touchant et aucune main n'étant près de lui ».

Il s'impliqua à la fin de sa vie dans la Society for Psychical Research dont il fut même président, c'est-à-dire qu'il étudiait les phénomènes paranormaux. Par exemple, il procéda à des études scientifiques pour tenter de comprendre les phénomènes qui se produisaient en présence des médiums Daniel Dunglas Home ou Florence Cook.”

Translation:

"Research concerning unexplained phenomena

Example of an experiment: 1) A new accordion, purchased by Crookes, is placed in a mesh box. 2) In the presence of Mr. Home, the accordion plays a melody "all by itself". The rest of the sentence cut at the end of the page is: "Then the instrument continued to play, no one touching it and no hand being near it".

At the end of his life, he became involved in the Society for Psychical Research, of which he was even president, that is to say, he studied paranormal phenomena. For example, he carried out scientific studies to try to understand the phenomena that occurred in the presence of the mediums Daniel Dunglas Home or Florence Cook."

The English Wikipedia was at some point in time (now this part has been deleted, a repeating fact that does not speak well for French intellectualism) somewhat better, as it stated, in particular, that:

Among the phenomena he witnessed were movement of bodies at a distance, rappings, changes in the weights of bodies, levitation, appearance of luminous objects, appearance of phantom figures, appearance of writing without human agency, and circumstances which "point to the agency of an outside intelligence"

There was also a link to a source, though not one that is very reliable. Fortunately what Crookes really did and what he wrote is nowadays available on archive.org. Let me describe Mr. Crookes activities that outraged the British Royal Society.

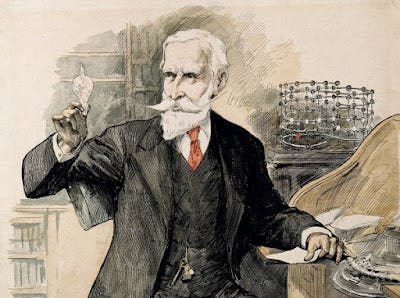

The Curiosity of Sir William Crookes

William Crookes

The first paper of William Crookes, on the subject that is of interest to us here, appeared in the July 1870 issue of Quarterly Journal of Science, (Available from archive.org) entitled “Spiritualism viewed by the light of modern science.”

Crookes decided to publish this paper only because there were already rumors circulating about his new research. He writes:

"That certain physical phenomena, such as movement of material substances, and the production of sounds resembling electric discharges, occur under circumstances in which they cannot be explained by any physical law at present known, is a fact of which I am as certain as I am of the most elementary fact in chemistry." (Italics, mine.)

Then he adds:

"My whole scientific education has been one long lesson in exactness of observation, and I wish it to be distinctly understood that this firm conviction is the result of most careful investigation. But I cannot, at present, hazard even the most vague hypothesis as to the cause of the phenomena."

It looks to me like a very honest appraisal with no assumptions or belief involved. Shouldn’t the honesty of a witness and researcher count when we have to decide whether his evidence is of interest to us or not? Then Crookes takes issue with Michael Faraday’s conservative and, I think, somewhat incoherent point of view:

"Faraday says, “Before we proceed to consider any question involving physical principles, we should set out with clear ideas of the naturally possible and impossible.” But this appears like reasoning in a circle: we are to investigate nothing till we know it to be possible, whilst we cannot say what is impossible, outside pure mathematics, till we know everything?"

Faraday and the Religion of Science

Michael Faraday

This circular reasoning of Faraday may have something to do with his religious beliefs – he had a strong confidence in the authority of Biblical Scripture. (Collin A. Russell, “Michael Faraday: Physics and Faith”, Oxford University Press, 2000) Once you rely on an authority, which you will never question, in one area of your life, you will tend to be an authoritarian in other areas as well. Once you abandon rationalism in one domain, it is all too easy to be irrational in another one. For Faraday Science, the way he saw it, was just another authority. Apparently the established and formulated physical principles were for him like a Scripture that should never be questioned.

No True Science Allowed! A Priori Assumptions Prevail

But, let us go back to the scientific curiosity of William Crookes. In the beginning, Crookes’ plans to conduct truly scientific experiments with respect to “spiritualist” phenomena were welcomed by the learned community. The attacks came only later, when the results of his experiments did not confirm their a priori assumptions.

Crookes published his second paper on this subject in the October 1871 issue of the same journal (available from archive.org). There he presented clearly his motivations and the philosophy behind his research. He started with stressing the role of Science, and he did it in an eloquent and, for me, really beautiful way:

Science alone makes steady progress in the present history of mankind. It is science which has transformed the world, though we rarely render her the justice and the gratitude that are her due. It is through her that we live intellectually, and even materially, at the present day. She alone can guide us and enlighten us.

William Crookes and The Strange Case of the Disappearing Camille Flammarion

Resistance to unconventional research further hampers scientific progress.

The motivations behind the work done by William Crookes and other curious researchers were described in the book “The Unknown” by a famous Frenchman, Camille Flammarion. That leads to the question: Who was Camille Flammarion?

Universum, C. Flammarion, gravure sur bois, Paris 1888

Charles Richet, who in 1913 won the Nobel Prize for physiology and medicine, wrote the eulogy for Camille Flammarion in 1925, opening with these words:

“Nous venons de subir une perte cruelle.

Voici que disparaît, en pleine puissance intellectuelle malgré son grand âge, notre héroïque ami Camille Flammarion.

Il fut un grand savant. Il fut un noble poète. Il fut un ardent ami de l'humanité et de la paix. Il fut aussi un des fidèles de notre sainte cause, et, comme il avait le culte de la vérité, les problèmes qui nous occupent ici ont animé ses dernières années.” "We have just suffered a cruel loss.

Translation:

We have just suffered a cruel loss.

Here is, in full intellectual power despite his great age, our heroic friend Camille Flammarion.

He was a great scholar. He was a noble poet. He was an ardent friend of humanity and peace. He was also one of the faithful of our holy cause, and, as he had the cult of truth, the problems that concern us here animated his last years."

Shockingly, French Encyclopedia Universalis ignores this famous French personality completely; fortunately, the website of Observatory Meudon gives us the relevant details:

Nicolas Camille Flammarion was born in 1842 at Montigny-le-Roi in the department of Haute Marne, France. He first studied theology, but early became interested in astronomy. At age 16, in 1858, he wrote a 500-page manuscript, Cosmologie Universelle, and became an assistant of LeVerrier (the man whose calculations had led to the discovery of Neptune) at Paris Observatory. From 1862 to 1867, he temporarily worked at the Bureau of Longitudes, then returning to the Observatory where he became involved in the program of double star observing. This project resulted in publishing a catalog of 10,000 double stars in 1878.

Flammarion was honored by the naming of a Moon Crater (3.4S, 3.7W, 74.0 km diameter, in 1935) and a Mars Crater (25.4N, 311.8W, 173.0 km, in 1973). Asteroid (1021) Flammarion was discovered by Max Wolf on March 11 …

In his book “The Unknown” Flammarion writes with true passion about the research of William Crookes and others:

This work is an attempt to analyze scientifically subjects commonly held to have no connection with science, which are even accounted uncertain, fabulous, and more or less imaginary.

I am about to demonstrate that such facts exist. I am about to attempt to apply the same scientific methods employed in other sciences to the observation, verification, and analysis of phenomena commonly thrown aside as belonging to the land of dreams, the domain of the marvelous or the supernatural, and to establish that they are produced by forces still unknown to us, which belong to an invisible and natural world, different from the one we know through our own senses.

Is this attempt rational? Is it logical? Can it lead to results? I do not know. But I do know that it is interesting.

“I do know that it is interesting.” The hallmark of a true scientific mind!

There is No Science Without Curiosity

William Crookes started his scientific investigations of phenomena that were - up to that point – considered to be outside the domain of science, simply because he saw that they were “interesting” and they incited his curiosity. There is no science without curiosity – I think one should always keep this in mind.

William Crookes and Frederick Engels: Dialectical Smearing

What kind of experiments was Sir William Crookes performing, and what was the reaction of the scientific community to these experiments and to their results? Before I answer these questions let me tell you about the reaction of one distinguished philosopher of this time, namely one Frederick Engels. In his “Dialectics of Nature” Engels had a whole chapter devoted to the subject of “Natural Science and the Spirit World”. The dialectic method is used there with the obvious purpose of smearing Crookes’ reputation with comments that have nothing to do with the experiment itself, probably with the hope that the reader would be warned off from actually checking the sources – the scientific publications of William Crookes himself. Obviously, this tactic works only on those who have no natural curiosity. Thus writes Engels:

The second eminent adept among English natural scientists is Mr. William Crookes, the discoverer of the chemical element thallium and of the radiometer (in Germany also called "Lichtmühle" [light-mill] ). Mr. Crookes began to investigate spiritualistic manifestations about 1871, and employed for this purpose a number of physical and mechanical appliances, spring balances, electric batteries, etc. Whether he brought to his task the main apparatus required, a sceptically critical mind, or whether he remained to the end in a fit state for working, we shall see.

In fact, this “we shall see” was completely misleading, because Engels did not discuss any details of the experiments; his intent was purely and simply to defame. Notice also how he uses the word “adept” right in the first sentence in order to create an initial influence in the mind of the reader. Just how this sort of “priming” works is studied extensively in modern cognitive science. Again we must ask the question: is lack of curiosity and lack of character co-related?

William Crookes and the Paranormal: True Science

William Crookes himself, on the other hand, described his experiments in as much detail as he possibly could, in a series of papers, and also in his book “The Phenomena of Spiritualism”. In particular, in a number of experiments, Crookes researched the phenomenon known today under the name of “telekinesis”.

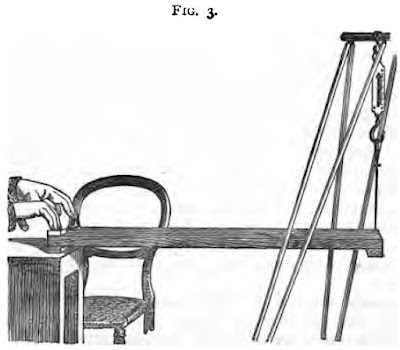

A “gifted medium”, Mr. Daniel Dunglas Home, exerted some kind of a force that could not be explained by the known laws of physics. One of the arrangements of the experiment is represented in Fig. 3 – taken from Crookes’ book, p. 15

What the spring balance measured, and what was recorded, could not be explained by the established laws of physics.

Curiosity Debunks the Debunker

What was the response of the scientific community? As Crookes remarks in his paper “Some further research on psychic force”, published in the “Quarterly Journal of Science”, October 1871, a leading scientific engineer of the United States, Mr. Coleman Sellers, objected that the mahogany board used by Crookes, given its dimensions, could not possibly have the weight of 6 lb, given by Crookes. It should have the weight of 13.3 pounds!

East African Mahogany (Khaya anthotheca)

Well, hold on a minute! This declaration made with such certainty incited my curiosity and so I checked the material properties of mahogany wood given in the tables that are available on the internet, and I came to the conclusion that it could.

The dimensions given by Crooks were 36x8.5x1 inches. This gives us the volume of 342 cubic inches. One foot has 12 inches; therefore we are dealing with about 0.2 cubic feet. According to a wood densities table that can be found on the internet, African mahogany wood has the density 30-53 lb/ft3, which, assuming that Crookes’ board was really dry, gives the weight of 6 pounds!

Certainly, the scientific engineer, Mr. Coleman Sellers, could have figured that out himself even without tables of properties available on the internet today. One suspects that he took a board of the correct dimensions, soaked it for a long time in water, and then weighed it so as to be “telling the truth” in his critique. That is how a lot of science is done, by the way.

The Apathy of Science

Anton Chekhov

Crookes commented on the reluctance and apathy of the scientific community regarding these truly astonishing effects:

I confess I am surprised and pained at the timidity or apathy shown by scientific men in reference to this subject. Some little time ago, when an opportunity for examination was first presented to me, I invited the co-operation of some scientific friends in a systematic investigation; but I soon found that to obtain a scientific committee for the investigation of this class of facts was out of the question, and that I must be content to rely on my own endeavours, aided by the co-operation of a few scientific and learned friends who were willing to join in the inquiry.

As noted already, at the beginning, when Crookes announced his plans, the reaction was, as a rule, positive: “if men like Mr. Crookes grapple with the subject, taking nothing for granted until it is proved, we shall soon know how much to believe.”

Yet, as Crookes noted in his second paper:

These, however, were written too hastily. It was taken for granted by the writers that these results of my experiments would be in accordance with their preconceptions. What they really desired was not the truth, but an additional witness in favour of their own foregone conclusions. When they found that the facts which that investigation established could not be made to fit their opinions, why, - ‘so much the worse for the facts.(Italics, mine.)

It was not therefore a surprise when these reactions changed to “The thing is too absurd to be treated seriously.” “It is impossible, and therefore can’t be true.”

The Attack of Science on Curiosity

Crookes also anticipated the attacks from those who are not curious because they know it all in advance. They know what is possible and what is impossible, and they are not in any need of experiments to verify what they are convinced about – like Michael Faraday mentioned above. Crookes analyzed the problem succinctly:

Many of the objections made to my former experiments are answered by the series about to be related. Most of the criticisms to which I have been subjected have been perfectly fair and courteous, and these I shall endeavor to meet in the fullest possible manner. Some critics, however, have fallen into the error of regarding me as an advocate for certain opinions, which they choose to ascribe to me, though in truth my single purpose has been to state fairly and to offer no opinion.

And:

Many people will say, ‘What is the use of seeking? You will find nothing. Such things are God’s secrets, which He keeps for Himself.’ There always have been people who liked ignorance better than knowledge. (…)

Other people may object that these chapters on the occult sciences are making our knowledge retrograde into the Middle Ages, instead of advancing towards the bright light of the future, foreshadowed by modern progress.

His reply to the last criticism makes an important point:

Well, then! I say that a careful study of these facts can no more transport us back to the days of sorcery, than the study of astronomy can lead us back to the times of astrology. (…)

Further on, Crookes asked:

Had the time really come? Was the way fully prepared? Was the fruit ripe? One can but begin, of course. Future ages will develop the seed.

I think we live in the “Future ages” and nothing has changed in the attitude of those who are not curious, those who are narrow-minded, and those who cannot live without being subservient to some authority, be it religion, be it “the mainstream science”, or both. Those people - sometimes they are scientists, sometimes administrators, and sometimes magicians - try to kill any curiosity, any research that dares to go beyond the boundaries of that which they declare to be “rational” – a totally irrational attitude, I would say.

To ensure science thrives, we must dismantle barriers to curiosity. First, cultural insularity, like France’s linguistic isolation, can be addressed by reforming education to prioritize English proficiency and encouraging multilingual scientific publishing to broaden access. Second, dogmatism must be countered by rewarding open inquiry over conformity, ensuring scientists like Crookes are judged by evidence, not preconceptions. Third, resistance to the unknown should be replaced with Flammarion’s passion for exploration, funding research into unconventional phenomena without prejudice.

A curious, open scientific culture welcomes questions, transcends borders, and dares to explore the unexplained. By fostering intellectual freedom—through education, collaboration, and tolerance for the unorthodox—we can safeguard science’s ability to unravel the universe’s secrets. Let us heed Crookes’ call: “Science alone makes steady progress… She alone can guide us and enlighten us.” The future of discovery depends on it.

Notes at the time of writing

P.S.1. 08-04-23 16:22 Seventies - These were Good Old Times

Try once more like you did before

Sing a new song, Chiquitita

P.S.2. 09-04-23 11:54 Noted this passage while reading McGilchrist - "The Matter With Things", chapter "SOME POTENTIAL CAUSES OF CONFUSION":

"However, we live in a society where talking about life is as much our defining quality as living it. And when it comes to articulating a philosophy, or a working model by which to understand our society and the wider world, that wisdom suddenly disappears in the mind of the public spokesman, politician or scientist in the need not to appear foolish. We become unnaturally self-scrutinising, and self-consistency suddenly becomes of prime importance. Regrettably we would rather speak falsely, if doing so means we do not seem to contradict ourselves: we realise that it is much simpler for our point of view to be dismissed as self-contradictory than untrue. Given this cast of mind, it is easy to see how one might easily argue one’s way into believing something which one knows perfectly well at a deeper desire to appear consistent to some – rather too simple – position." (bold - mine)